Echoes of an earlier pandemic

Given the sweep of the 1918 influenza pandemic, dubbed the “Spanish flu” in popular media at the time, it may seem odd to find that the ordeal barely garnered a mention (just one sentence, in fact) in that year’s Potsdam Normal School senior class book—sandwiched between gaily references to the busy social calendar of the time. Perhaps owing to the social mores of the time, or the much larger impact of the recently concluded Great War on the campus community, the pandemic barely registers among the year’s events as recorded.

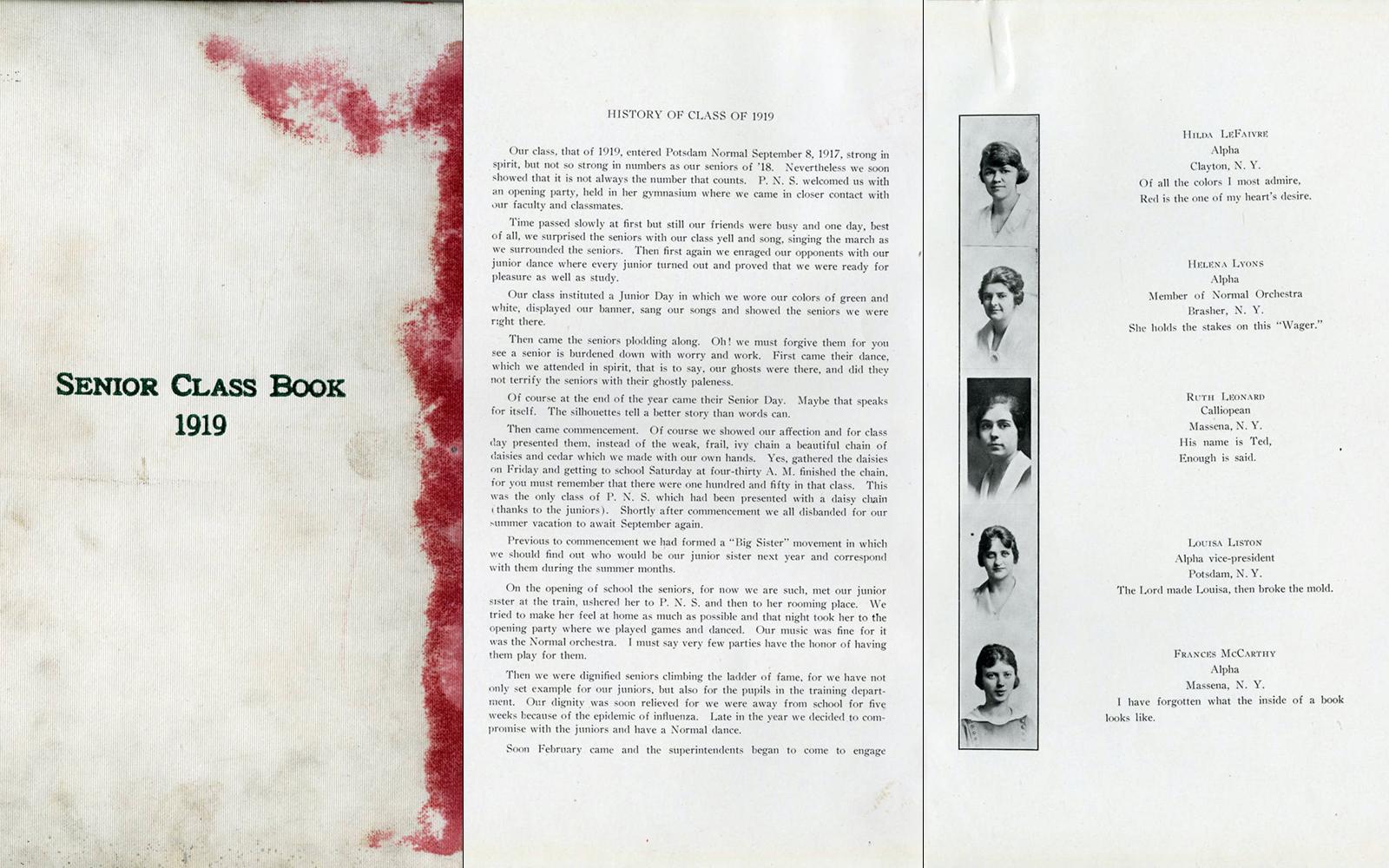

In her class history, Louisa Liston (Class of 1919) writes, “Then we were dignified seniors climbing the ladder of fame... Our dignity was soon relieved for we were away from school for five weeks because of the epidemic of influenza. Late in the year, we decided to compromise with the juniors and have a Normal dance.”

Seen here is the Crane Class of 1918, with few men, due to World War I. In the window are Julia Crane and her sister Harriet Crane Bryant, flanked on the right by Helen Hosmer. Just a few months later, the village would be struck by the second wave of the influenza pandemic and the Normal School would close for five weeks (Source: College Archives).

Local newspapers from that time provide more insight on how the two local institutions of higher education in Potsdam, N.Y., were responding to the rise in illnesses—variously attributed to the Spanish flu, grip, colds and pneumonia. An unbylined article in the October 9, 1918 Courier and Freeman described how 25 soldiers in the Clarkson College Student Army Training Corps were being treated for colds, although none had yet developed the severe pneumonia symptoms that ultimately would prove so fatal for many. The officer in charge ordered a quarantine that will sound familiar to today’s students, permitting the Clarkson cadets only to go to “the college, their barracks and their club room, but nowhere else.”

Local newspapers from that time provide more insight on how the two local institutions of higher education in Potsdam, N.Y., were responding to the rise in illnesses—variously attributed to the Spanish flu, grip, colds and pneumonia. An unbylined article in the October 9, 1918 Courier and Freeman described how 25 soldiers in the Clarkson College Student Army Training Corps were being treated for colds, although none had yet developed the severe pneumonia symptoms that ultimately would prove so fatal for many. The officer in charge ordered a quarantine that will sound familiar to today’s students, permitting the Clarkson cadets only to go to “the college, their barracks and their club room, but nowhere else.”

Across the street (at its location at the time), the Potsdam Normal School, with many male students and faculty having been conscripted into service, the nearly all-female student body reported few cases at that point. “It was stated at the Normal yesterday that its attendance had not been materially affected, in fact so far as absences were concerned, the records showed that the percentage of students absent through illness was very slight, no more than usual,” the Courier reported.

Just one day later, the two colleges closed as a precaution, and the following day, the Village of Potsdam Board of Health further enacted a ban on gatherings. “The majority of Normal students have returned to their homes,” the Courier reported. “The action, fortunately, was taken before any considerable number of cases developed in the student body, and the students, if they contract the disease, will have the advantage of care in their homes where facilities will certainly be far better than they would be here.”

Pages from the 1919 “senior class book” from Potsdam Normal School can be seen here (Source: College Archives).

The flu continued to spread, with an estimated 400 cases locally at the height, eventually taking the lives of six Clarkson students from the training unit. The military hospital was so overwhelmed that the local Masonic Temple opened its doors to accommodate additional patient beds, and local residents dropped off donations of food and supplies.

On October 30, 1918, the Courier reported that the Board of Health had yet to lift the quarantine, and added that while new cases were declining, the numbers of deaths from those who had taken ill over the prior weeks had yet to abate. “While locally conditions are better, the heavy toll which the epidemic has taken is evidenced by reports from correspondents of the Courier in neighboring towns. It is doubtful if there ever was an issue of the paper in which as many deaths have been recorded as in this issue,” the piece reads.

Students take in their afternoon tea at the Potsdam Normal School, circa the early 1900s. (Source: College Archives).

The local quarantine was finally lifted in Potsdam on November 10, 1918, and the two colleges were set to follow suit the following day—though they ended up taking an extra day off to allow for the Armistice Day celebrations marking the end of the war. “The Normal and Village schools were scheduled to open Monday, but in view of the celebration that day no one really had the heart to ask anybody to go to school and studies were therefore resumed yesterday.” To allow students to catch up in their studies, Potsdam Normal School later announced that it would reduce its holiday breaks for the rest of the academic year.

In the pages of history, no deaths among Potsdam Normal School students or faculty are attributed to the Spanish flu. World War I, however, claimed the lives of 12 students and alumni, of the 207 who served in the U.S. Army during the war. Left unrecorded are the untold number of influenza deaths among family members of the students, faculty and staff. After having their lives come to a brief halt during the quarantine and finally witnessing the momentous end to World War I, the Class of 1919 ultimately became the College’s first and only all-female graduating class. Its graduates also saw an important place for their alma mater and for their teaching profession in the transformed world that they were entering into.

“Not only has the world war created a new set of ideals for the whole world but it has brought about radical changes in education, politics, economics and social conditions,” wrote Marian Putnam in an inscription for the class gift. “The Normal School will be one of the important channels through which these new ideals will be brought to the people, to give a greater number of people an opportunity to obtain an education.”

—Article by Alexandra Jacobs Wilke