Potsdam researchers study an insect imperiling New York forests

As the emerald ash borer eats its way through Northern New York forests, SUNY Potsdam’s Dr. Jess (Rogers) Pearson and her team are getting out ahead with tools to understand and hopefully curtail the threat. Funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the team has released parasitoids that attack the borer at multiple experiment sites in St. Lawrence County.

The borer is on the march through forests across the U.S., its larvae damaging trees by feeding on the phloem, a tissue that transports sugar and nutrients from the leaves to the rest of the tree. Stricken forests show dead branches, small leaves and thin crowns. The borer’s impacts on ecosystems are still being revealed. And scientists worry that profound shifts, both foreseeable and unknown, could shake forests that lose their ash trees. Ash trees are foundational to eastern forests—particularly wetland ecosystems—and their loss disrupts and alters natural balances, habitat and food sources.

“Because the borer takes 3 to 7 years to really destroy a tree once it’s infested, we’re just starting to see the large-scale damage."

She and her team are working in the forests of Jacques Cartier State Park, Robert Moses State Park, Coles Creek State Park, and the Brasher State Forest, comparing tree health, measuring borer damage and determining how well the parasitic biocontrol agents survive and do their job of protecting large trees, which have a hard time surviving an attack. Pearson hopes to gather the data to support a treatment program that could be applied broadly down the road—combining initial insecticide treatment to knock back the borer with biocontrol agents to finish off the defense.

“Our hypothesis is that once borer densities decline and the populations of our biocontrol agents increase, one could stop treating with insecticides because the biocontrol agents would take over,” explained Pearson, an associate professor of environmental studies at SUNY Potsdam.

Biocontrols—or the deliberate use of natural enemies—have been successful against invaders like the spongy moth and ash whitefly, but it has been challenging to contain the emerald ash borer this way. Infestations are hard to locate until the pest has become so well established that biocontrol agents don’t have much of a chance of catching up before the forests lose their large, valuable, seed-bearing trees.

Pearson has sat on the St. Lawrence County Emerald Ash Borer Task Force since the insects first appeared in green and black ash forests in 2017. Her project is an ongoing partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and works in conjunction Akwesasne Mohawk tribal members, who use the ash for basket making and recently felled trees to monitor for the borer.

Pearson, who spearheads the project with SUNY Potsdam Biology Professor Dr. Glenn Johnson, is assisted by students Alyssa Card ’26 and Kelly Bloom ’25, both environmental science majors. Card and Bloom are working full time as technicians, trapping and monitoring the borer while assessing levels of the biocontrol agent to see if the population is successful.

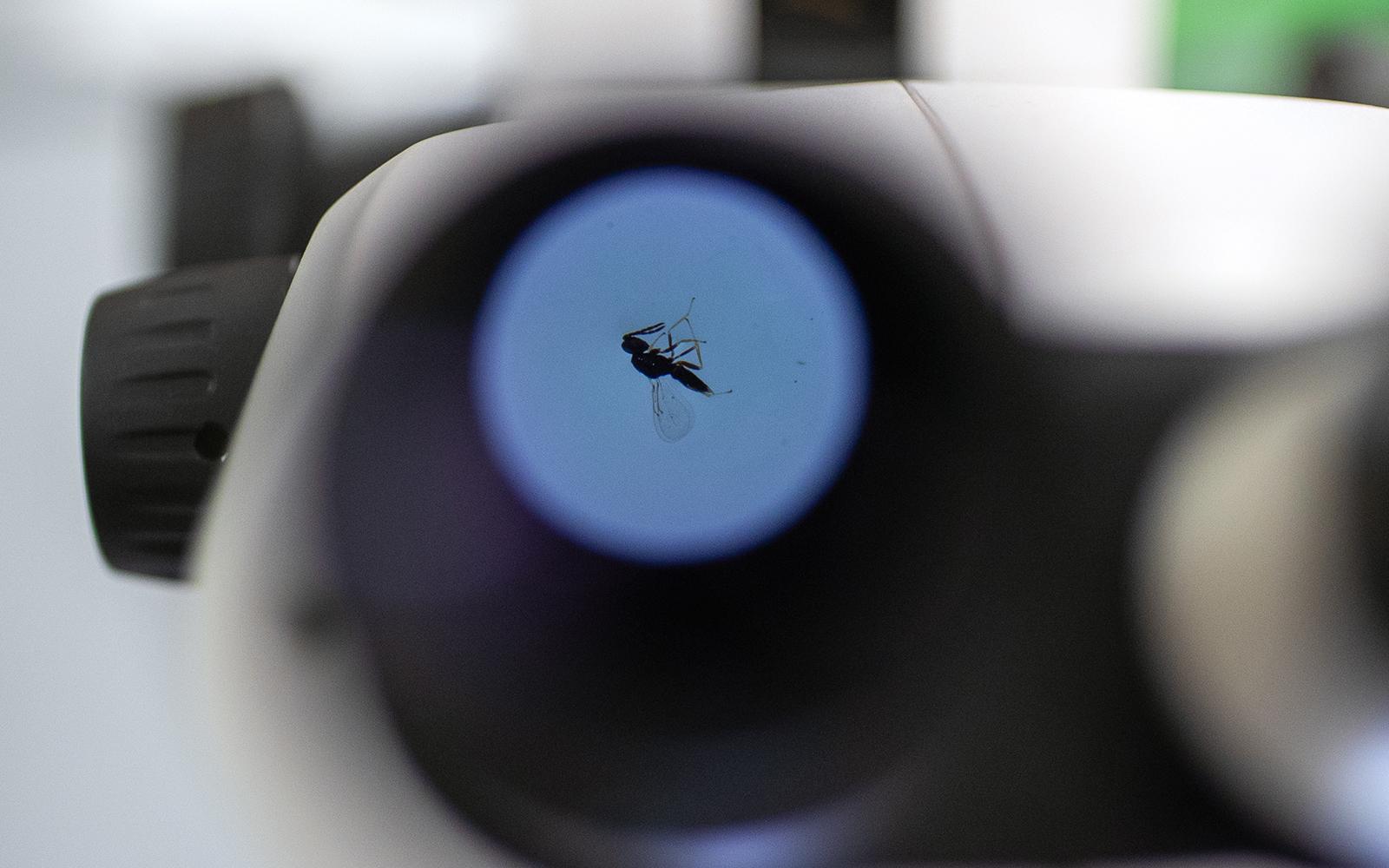

Kelly Bloom ’25 uses a microscope to examine a parasitic non-stinging wasp (Platygastroid wasp) in SUNY Potsdam’s Stowell Hall. The wasp is one of the insects captured in a pan trap while looking for the Tetrastichus planipennisi, a natural predator of emerald ash borer larvae.

A parasitic non-stinging wasp (Platygastroid wasp) is seen through the lens of a microscope in SUNY Potsdam’s Stowell Hall. The wasp is one of the insects insects captured in a pan trap while looking for the Tetrastichus planipennisi, a natural predator of emerald ash borer larvae.

The team will be collecting and crunching data in the months ahead as part of the multi-year, multi-state partnership.

“We’re not exactly sure what the long-term solution is yet,” Card said. “Our work is to assess the extent of the infestation locally and the health of ash. One of our main goals this summer is to see if the biological controls were successful.”

The beetle is native to northeastern Asia and was first spotted in Michigan in 2002. The USDA’s outlook on the pest has been both grim and hopeful. The department notes that once an area is infested, the healthy trees are often simply the last to die and will “quickly succumb” to the borer within a few years. However, some trees do remain healthy, and the USDA is experimenting with the propagation of these resilient trees.

The ability to kill healthy trees makes the shiny green beetle one of the most damaging insects to invade North American forests, according to researchers at Purdue University.

The repercussions of the borers’ spread are ecological, but also economic and cultural. Eastern U.S. forests produce about 114 million board feet of ash lumber each year, valued at $25 billion, with uses ranging from furniture to tool handles to paper. Indigenous practices are deeply rooted with the tree.

“Black ash trees hold enormous cultural significance for the Saint Regis Mohawk,” Pearson said. “So, trying to find solutions to EAB is important.”

Article by Bret Yager. Photos by Jason Hunter