Potsdam Students Hit the Road to Hunt for Clues to an Astonishing Past

A mere dot in the stark and rising landscape of El Capitan in the Guadalupe Mountains of west Texas, Ty Paddock ’25 stared at the slopes of the enveloping mass and realized he was witnessing an ancient reef system formed when the land all around him was the bottom of the Delaware Sea, some 275 million years ago.

His eyes scaling the slopes, calculating layers of history, Paddock was struck by the dramatic way that landscapes change over time and simultaneously, by the fact that he would be standing deep underwater.

A geology major with a minor in biology, Paddock was part of an excursion of 11 SUNY Potsdam students and three faculty members who decided to forgo pool time and instead spend spring break exploring significant geological sites of west Texas and southwestern New Mexico. The group plied acres of ground in search of clues and fossilized life forms, climbed 2,000 feet in elevation and hiked 10 miles roundtrip along the way. For geology major Makenzie Kuntz ’26, every blister was worth it.

“Something that finally clicked for me was the change in rock as you go from a deep marine setting to land,” said Kuntz. “As we were hiking the Permian Reef Trail, you can see the rocks change from a deep marine to a shallow marine setting as you hike up the reef. You can see the rocks go from a sandy limestone to a nice, layered limestone, and then more massive limestone. Finally, it turns to a sponge-boundstone due to the reef being made by sponges instead of coral. No matter how many times I had my professors explain it to me, I just could not make sense of it until I saw it on the Guadalupe Mountains.”

The group measured and logged fossilized sponges, examined debris flows and sediments and even solidified a direction for future studies.

“I have been struggling with deciding what type of geology I would like to focus on, and after this trip, it's clear that hot rocks are so much more meaningful to me than anything else,” Kuntz said.

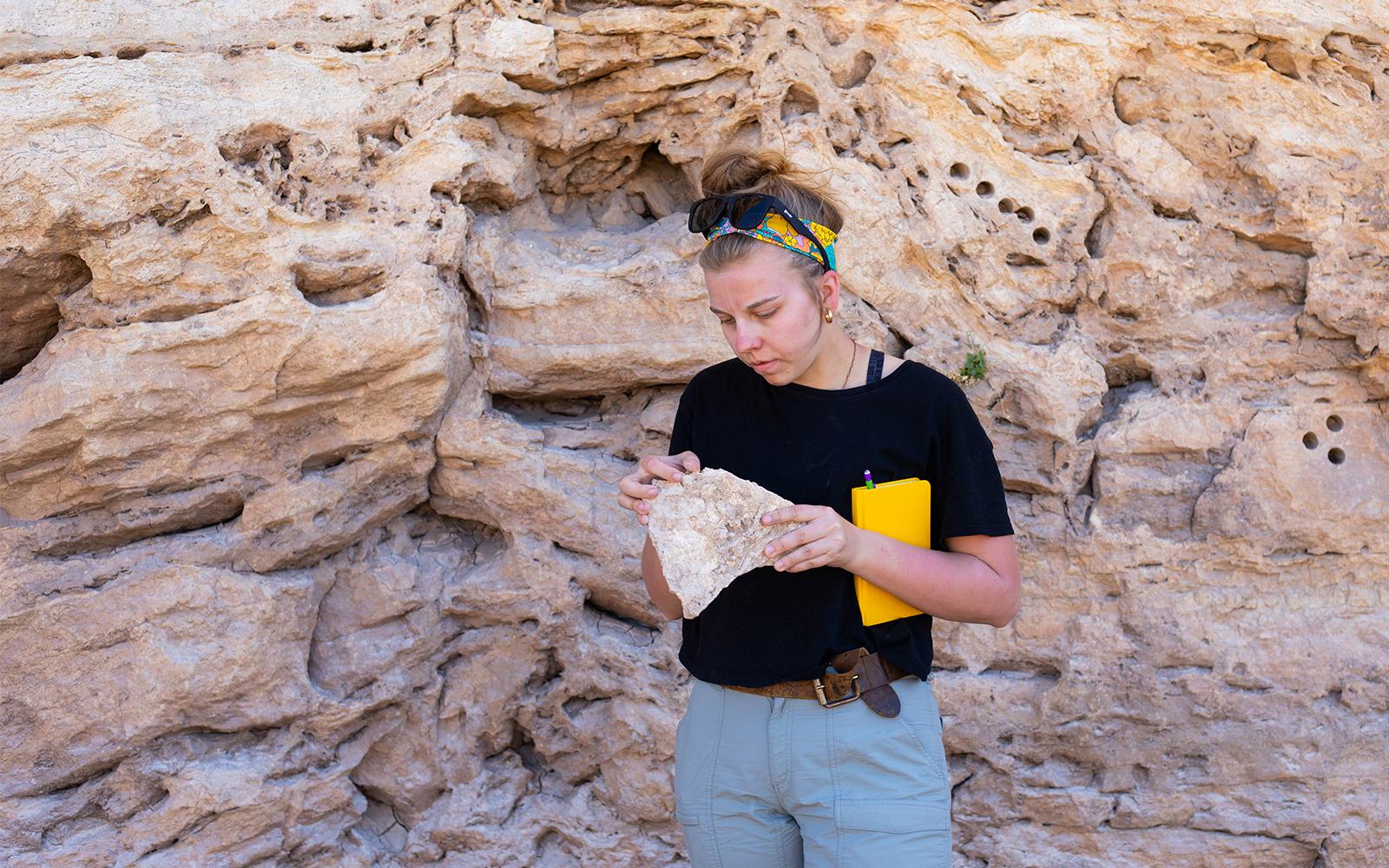

Makenzie Kuntz, left examines a rock with Dr. Christian Schrader.

The clarity took hold as Kuntz lost herself in the explosive past of Kilbourne Hole, a volcanic crater 24,000 to 100,000 years old that spewed bombs of sparkling green and yellow olivine mineral, leaving measurable dents in the ground.

The group stood in the world’s largest gypsum sand dune system at the White Sands National Monument in New Mexico. Dwarfed by 275 square miles of glittering desert, they studied erosion patterns, sediment transport, and dune formation in the Tularosa Basin—an enclosed basin where water enters but does not leave except through evaporation. And they ducked underground to examine the formation of Carlsbad Cavern and stand in the soaring, cathedral-like space with stalactites for a ceiling.

Dr. Michael Rygel, Dr. Page Quinton, and Dr. Christian Schrader, professor and associate professors in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, respectively, spearheaded the excursion with the goal of blowing a mind or two.

“Why take students to the field? The most important reason is to give them a sense of the size, scale, and complexity of natural systems. It’s one thing to read about it in a textbook, another to stand on the rim of a volcanic crater."

Geology Professor

Putting the Pieces Together

Alyssa Card '26, an environmental science major with a geology minor, found that the trip informed a different research project she is working on with Rygel and Quinton to understand a similar shallow sea from the Devonian age—one that is located in present-day Montana. Climbing an ancient reef frozen in stone made things come together in a new way.

“This trip was such an amazing opportunity to both experience true geology field work techniques as well as learn about the environments of both past and present Texas and New Mexico,” Card said.

More than two-thirds of the trip’s costs were covered by a National Science Foundation grant, the newly endowed Vedder Foundation at SUNY Potsdam, and the Collegiate Science and Technology Entry Program (CSTEP), with Kilmer Lab support dedicated to assisting future research building on the trip’s discoveries. The funds put the trip within reach for the students, Rygel said.

“Most of the students in the course are geology and environmental science majors, but we also have students from several different majors,” he explained. “Overwhelmingly, they are early in their educational career; the vast majority are sophomores—none of them have looked into a volcano, or been in a desert in the middle of dune fields. Some of them chose to climb a mountain. We took them underground into a cave. For many of them, this experience was completely new. They saw oil wells being drilled, natural gas flares, and water being pumped out of springs to do all these things. They saw how it works out in the world. Then we cooked them dinner every night and got to know them as people. We hope we broadened a lot of horizons and hope we built bonds that will last the rest of their lives.”

Places to Find Answers

So why care about geology? For one thing, the Earth still has a lot of mysteries to bond over. Or, as Kuntz put it: “This is where these connections are formed, when you're stuck in the desert and accidentally eat sunscreen thinking its mayo, or bond over the blisters you all need moleskin for.”

Plus, Schrader said, you can take information from one geological event—such as the lateral blast of the Mount Saint Helens eruption in 1980—and extrapolate across time and space to identify patterns that add to foundational knowledge of how the Earth formed and how it sometimes destroys itself. Then, you can take that knowledge directly into arenas ranging from the environmental field to energy exploration, depending on your career goals.

Geologists deal with immense, complex systems with a lot of room for the mind. The datasets they work with are incomplete, and more answers are needed to help piece together the puzzles of how things function directly under our feet—and on the high ridges.

“You get to explore these big, crazy questions,” Quinton said. “You get to go into the field, climb mountains, and work above mountain goats to answer questions about how the Earth’s climate has changed over time, for instance—important questions of societal relevance, where you are looking for answers in some of the most amazing places in the world.”

Article by Bret Yager, Photos by Ayisha Khalid' 24