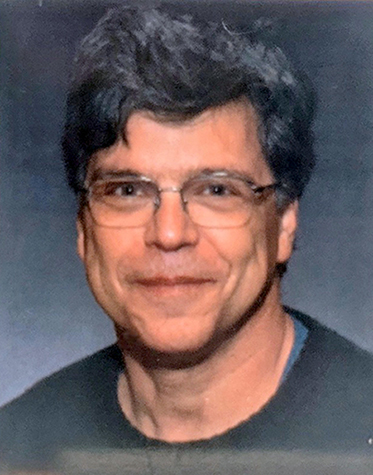

Not many people spend 30 years in the trenches of an emergency room, but Dr. Stuart Etengoff ’82 wanted to stay close to those most damaged and in need of immediate help. Three decades into the siege that does not end, he is finding deeper reasons for why he is there.

“After doing this for 30 years, you start seeing the good in people. It’ll help us get through this if we start seeing that goodness," Etengoff said.

After graduating from SUNY Potsdam with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1982, Etengoff continued his education at the New York College of Osteopathic Medicine, then completed his residency and the first 10 years of his career at Pontiac Osteopathic Hospital in urban Pontiac, Mich. He went on to ease suffering in emergency rooms in rural areas of the Wolverine State before settling at the McLaren Clarkston Emergency Center, about an hour outside of Detroit.

After graduating from SUNY Potsdam with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1982, Etengoff continued his education at the New York College of Osteopathic Medicine, then completed his residency and the first 10 years of his career at Pontiac Osteopathic Hospital in urban Pontiac, Mich. He went on to ease suffering in emergency rooms in rural areas of the Wolverine State before settling at the McLaren Clarkston Emergency Center, about an hour outside of Detroit.

Through its ups and downs, something of the soul of the place has held him there.

An ER physician is hard-wired to endure, and must find ways to process the long hours and the witnessing of human suffering. These days, it’s not just about the drive to save lives, but increasingly, the cure lies where it was in the first place, with people — before everything got buried under busy-ness and the excitement of career.

And so, for Etengoff, the personal becomes increasingly important. Over time, he has gravitated more toward the simple joy of talking with people, slowing down where possible and visiting with them and hearing their amazing stories — like the patient who was a medic when U.S. forces took Iwo Jima in World War II. Other friendships with school teachers, pilots, diesel mechanics, are also adding to an intangible sense of value, gathered as they are from the decades spent helping in one area.

It was his relationships with SUNY Potsdam professors and hiking buddies, and the feel of wild lakes that have stayed with Etengoff over nearly half a century — a clue to what we will remember when the rest has faded.

“I loved Potsdam and the Adirondacks. It was a small school where you would get to know your professors and meet with them and learn directly from them, which, for the way I learn, is very important,” remembered Etengoff, who grew up in Buffalo. “I canoed every one of those little lakes up there. It was a great place to be a teenager and in college.”

While healthcare workers are often identified as the “first line,” Etengoff lauds the often invisible people making the world go round — food service workers, bus drivers, janitors, housekeepers and grocery clerks. He notes these vital workers are toiling for minimum wage, with minimal protection.

The news surrounding COVID-19 is relentless, and we still know so little about the disease. Etengoff’s training and expertise make him cautious about the rush to reopen the nation.

“I’ve worked in the inner city and rurally, and I’ve seen people sick and with terrible problems,” he said. “But with this, there are so many young people who shouldn’t be sick who are getting sick and dying, and there are more and more children.”

“I’ve worked in the inner city and rurally, and I’ve seen people sick and with terrible problems,” he said. “But with this, there are so many young people who shouldn’t be sick who are getting sick and dying, and there are more and more children.”

We have only about 60 days of COVID-19 statistics in the U.S., Etengoff said. The medical community is learning new things almost daily, but is only beginning to grasp surprising aspects of the disease — like massive strokes in young people, and the possibility of long-term effects on the kidneys and respiratory system. There is little data to work from, the learning curve is steep, and each place is different.

“You just can’t predict what will happen and that’s the problem,” Etengoff said. “I understand the frustration. People have to pay bills; they have to go to work. But at this point, we’re only 90 days into this.”

The best approach to the pandemic is still daily prevention and minimalization of contact — if not for yourself, then for those who are close to you, Etengoff said. His colleagues on the front lines perform self-care as best they can, but their biggest concern is not for themselves; instead, they fear catching the virus and bringing it home to family and friends. Some haven’t seen their children or other loved ones in two weeks because they want to keep them safe.

Too much has been overturned too quickly, and our methods of processing change have been swept up in the whirlwind. Those experiencing loss most directly are left unable to properly grieve.

“Families aren’t getting to see people in hospitals,” Etengoff said. “You’re putting people in, knowing that some of them are never going to see their family again. There are no funerals, no ceremonies.”

But every day Etengoff is convinced: Brave and selfless acts are happening everywhere and the good stories will get us through. Indeed, they may be as priceless as the daily influx of medical information which gives us the tools to put up a proper fight.

“After doing this for 30 years, you start seeing the good in people,” he concluded. “It’ll help us get through this if we start seeing that goodness. There are people out there calling their neighbor to see if they need groceries, driving people around, taking your dog for a walk, and doing volunteer work. I think it’s the simple things that are bringing communities together. We are all united; we want the same good outcome. There is a lot of good out there.”

Article by Bret Yager